Chapter 12: Semi-Fascism: The New State of 1939

"The new regime was by far the most centralized in Spanish history. Only the provinces of Navarre and Alava, both of which had abjured Basque nationalism and made major contributions to the Nationalist victory, retained a degree of provincial self-administration. The regional autonomy statutes for Catalonia and the Basque provinces were completely annulled, and the two “special regions” were, again with the partial exception of Alava, brought directly under a uniform pattern of central administration. In the case of Catalonia, which was not occupied until near the very end of the war, a special occupation administration held sway from January 26 to August 1, 1939.' The use of Catalan and Basque in publications, the courts, and even in religious services was generally prohibited,"

"Sudden expansion of the state system required rapid employment of thousands of relatively untrained personnel, resulting in a rather low level of competence and probably also encouraging the spread of corruption, which began to plague the regime during the first year of peace. A decree of August 25, 1939, reserved most state employment for active Nationalists, stipulating that 80 percent of all ordinary state jobs would be reserved for veterans of the Nationalist Army, civilians who had made special sacrifices for the cause, former prisoners of the Republicans, and relatives of victims of the Red terror."

"The leaders of the new Spanish state firmly believed that the European order was moving toward national “organic” authoritarian regimes, and for the first four years after the Civil War Franco ran the entire government as though it were an army, ruling by leyes de prerrogativa, personal decrees issued by the chief of state. A new Ley de la Jefatura del Estado (Law of the Head of State) was published on August 9, 1939, which further expanded Franco's powers as originally defined by the decree of January 29, 1938. The new measure declared that the powers of government were permanently confided” to Franco, who was categorically relieved of the need to submit new legislation or decrees to his cabinet when “urgent problems” required it.* Revised statues of the FET, issued a few days earlier, further extended his direct control over the state party. Though post- war Spanish society and institutions were not at all totalitarian in terms of complete government control, the new government was in its own formal theory a more direct personal dictatorship than those of the Soviet Union, Italy, or Germany."

"Franco completely reorganized his cabinet on August 8, 1939, retaining only two of the incumbents, Serrano Súñer and Alfonso Peña Boeuf, the professional engineer in charge of public works. The principal changes had to do with the Falange and the military leadership. Five cabinet posts were given to Falangists and neo-Falangists, compared with two in the preceding government, reflecting an effort to approximate, at least symbolically, the new fascistic era that seemed to be dawning in European affairs. "

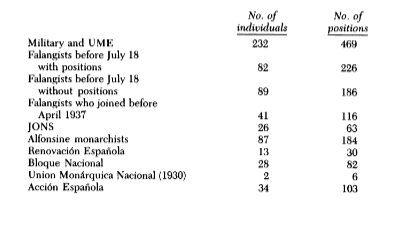

"Though some at first dubbed this a Falangist government, it was obviously no such thing. The new cabinet represented Francos regular balancing act between the various ideological “families” of the regime. The nearest thing to a true concentration of power was in the military, yet even they held little corporate power, the individual military ministers being carefully selected in terms of personality, loyalty, and political identity (or lack of it) to fulfill what were primarily individual roles. During the entire first phase of the regime down to 1945, military personnel would hold 45.9 percent of the ministerial appointments and 36.8 percent of all the top governmental positions,? concentrated primarily in the armed forces ministries and in Interior, which dealt with the police. Falangists, by comparison, would hold 37.9 percent of the ministerial appointments and only 30.3 percent of all the top administrative positions, concentrated above all in the party administration, Labor, and Agriculture."

"The new permanent statutes of the party maintained indefinitely the parallel system of Falangist Services and Delegations.'” They created only

the illusion of a parallel state structure, for most of the Falangist national

delegates had no governmental authority whatever. "

"By 1939 the FET organization claimed a nominal active male membership of approximately 650,000.' Most younger men of active age who hoped to get ahead in politics, obtain state employment, or flourish in various lines of professional or economic activity found it expedient to sign up, and FET membership would continue to increase for three more years, reaching an all-time high of 932,000 in 1942.* The FET bore responsibility for political indoctrination of the population and for providing the political infrastructure of the entire system.’ Nearly all the new provincial governors and mayors were nominal members, but the bulk of the active male membership was relatively passive and only rarely mobilized. Hundreds of disillusioned camisas viejas, finding the new Spain not at all the dynamic and revolutionary national syndicalist system to which they aspired, had dropped out of active participation."

"In general, FET administration was content with a nominally large but little mobilized and basically passive membership. “4

The regime placed considerable emphasis on youth, giving it frequent attention in state propaganda, and in theory this was another important focus of Falangist mobilization. "

"Against the advice of other camisas viejas, Sotomayor accepted the leadership of the SEU. He and his handful of fanatical young associates planned a semiautonomous mass student organization to promote national revolution. "

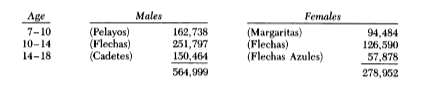

" long delay ensued before the official organization of the Frente de Juventudes to ensure its restriction and subordination. It was not officially formed until December 6, 1940,'* and even then it never became a fully developed mass organization on the national level. The Frente de Juventudess most extensive activities would have to do with camping and sports. Its main division, the Falanges Juveniles de Franco, according to its own statistics never mobilized more than 13 percent of the boys and 8 percent of the girls of Spain between seven and eighteen years of age—even at its height.'? Membership was voluntary and members were primarily the children of ardent Nationalists, but even many of these received only limited political indoctrination.

To compensate for the feeble development of political theory thus far, an Instituto de Estudios Politicos was created under the FET on September 9, 1939. It was designed as a sort of brain trust for the new regime, combining features of an advanced training school for high-level party leaders with those of a study institute for policy and theory. "

"Yet of all the regime' political objectives, probably the most important during the autumn of 1939 was the negotiation of a new concordat with the Vatican, a proposal already broached before the end of the Civil War. Franco saw this as the logical culmination of his neotraditionalist religious policy, roofing the solid edifice of Catholic support that he had built for his new system. The government annulled the old Republican divorce law in September and on December 1 resumed the state ecclesiastical subsidy. Talk among Falangist anticlericals about a national church was quieted, and even Arriba, the central Falangist organ, underlined the mutual desirability of a treaty with the Vatican. A circular from Muñoz Grandes to all Falangist provincial chiefs on October 25 forbade imitation of such Nazi styles as “Nazi uniforms, goosestepping, raised arm ovations, etc.” in keeping with the spirit of the Spanish diplomatic offensive. If the Vatican had been willing to sign a concordat with Germany during Hitler's first year as chancellor, Franco felt that it ought to be all the more interested in such an accord with so ultra-Catholic a state as Spain during its first full year of government."

The Armed Forces

"The military not only provided the key martial underpinning of the state but also administered the repression and led the police forces, were responsible through ministerial appointments for much of national reconstruction and the new industrialization program, and even provided some of the key symbols and ideological components of the regime through the doctrine of military caudillaje.

By 1939 the officer corps of the Spanish military and their leadership was in considerable measure a creation of Franco. Though senior officers antedated the Civil War Nationalist Army,” a new corporate group had been forged in one of the harshest of military experiences, bound to and identified with its Generalissimo. During the war Franco had astutely downplayed rewards and promotions, emphasizing common service and sacrifice, so that it had not been uncommon to find colonels commanding divisions and brigadiers entire corps. This had proven effective, focusing attention on performance, but a major round of promotions took place after the fighting was over that involved restoration of the ranks of lieutenant general and full admiral, abolished by the Republic. Though salaries remained low,* officers enjoyed special privileges, particularly their access to the well-stocked and low-priced commissaries that were a special contrast in a country beginning to suffer grave shortages. Former enlisted men were given preference in the newly announced government hiring quotas. On the whole the military were content and would remain the backbone of the regime, with little dissidence, until the time of Franco's death. They took pride in their overwhelming victory and in the place of honor they held in the new system.

It was this privileged status that made it possible for the only public signs of discontent in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War to be ex- pressed by two of Francos most restive generals, Yagiie and Queipo de Llano. "

"The Army alone had come to number over 900,000 by the end of the war. On January 24, 1939, Franco decided to cut the postwar force to a nominal 24 divisions formed in 10 corps, one for each of Spains eight regular territorial military districts plus two for the Moroccan Protectorate. At its lowest point Army manpower sank to about 230,000 early in 1940, in addition to 20,000 Moroccan troops. The spread of World War II soon encouraged as much expansion as the slender resources of the new state could afford, however. For much of the war, about 400,000 troops were maintained, the Army numbering about 365,000 in 1945. The numbers in the officer corps, nominally around 15,500 in 1940, rose to nearly 26,000 by 1945. Thus the old institutional scourge of a bloated officer corps, temporarily eliminated at least in part by the Republic and the Civil War, quickly reemerged under the new regime, because of the pressure of World War II and of domestic political considerations."

"During the first months of peace the regime had great visions of restoring Spains long-lost sea power. On September 8, 1939, it announced a ten- year naval armament program that proposed to build 4 battleships, 2 heavy and 2 light cruisers, 54 destroyers, 36 torpedo boats and 50 sub- marines within the next decade...and had to be abandoned soon after it was first an- nounced. Between 1940 and 1945 the shrunken Spanish economy was able to construct only 3 submarines and 6 corvettes, while a fourth sub- marine was purchased from Germany. Two new destroyers were begun but only completed later. Naval personnel grew only slightly during World War II, increasing from about 1,600 officers and 20,000 men in 1940 to more than 2,600 officers and 23,000 men in 1945.%

Not to be outdone in ambitious planning, the new air force minister, Yagiie, presented a proposal to the government in October 1939 that would involve the acquisition of 3,740 combat planes during the coming decade. This proposal found less favor than the grandiose naval plan and was soon reduced by more than half, fixed at a rate of 150 planes per year that would involve little more than normal replacement of worn-out material. Thus the Air Force remained of modest dimensions, growing from 3,800 officers and 25,000 men in 1940 to nearly 4,000 officers and almost 31,000 men by 1945.

Immediately after the Civil War the police underwent more extensive reorganization than the armed forces proper. At one point Franco considered abolishing the century-old national constabulary, the Guardia Civil, in favor of a new unified force for both towns and countryside, but was dissuaded. Instead, the Carabineros (border patrol) were merged with the Guardia Civil, the latter retaining its name and distinctive identity and uniforms. It numbered approximately 60,000 by 1941, or about 20 percent more than the two combined in 1936. The institution was placed under full military discipline and the command of career Army officers, who also held numerous intermediate posts. The Republics special urban Guardias de Asalto were replaced by a new system of urban Policfa Armada (Armed Police), which numbered 17,000 by 1942. All security forces together had an only slightly larger enrollment in the early 1940s than they had under the Republic, though they were employed much more vigorously.

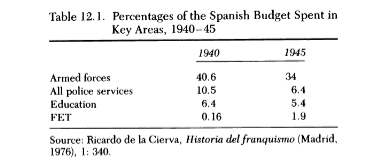

The goals of streamlining and modernizing the armed forces were not, however, being met in any way, nor could they under the straitened circumstances of the Spanish economy. Most of the budget for the Army and Navy was still being spent on personnel, given the continued bloat in the officer corps. All that the regime managed to accomplish in fiscal terms— and this was not unimportant—was to reduce somewhat the armed forces’ portion of the national budget"

The beginning of autarky

"he effort to restore full production encountered major obstacles. This was not because the Civil War itself had been enormously destructive in strictly economic terms. Its results, for example, could not in any way be compared with the massive destruction inflicted on areas of central and eastern Europe during the six years that followed. The firepower available to both sides had been modest compared to that routinely employed in World War II, and with the notorious exception of Guernica, Spanish cities had never been heavily bombed. Even so, the losses had been costly and were proportionately heaviest in shipping and transportation, with nearly 30 percent of the nations maritime tonnage destroyed (primarily by the attacks of the Nationalists and their allies) and half the railway locomotives lost. Eight percent of Spains housing and more than a third of the livestock had been lost. Though no more than 6 to 7 percent of the total national wealth had been directly destroyed, the disruption of production was very great. By 1939 industrial output was 31 percent less than in the last prewar year, agricultural production had declined by 21 percent, the labor force had fallen by half a million, and per capita income by approximately 28 percent.* Spain thus faced a major task of reconstruction and development, compounded by the long-term effects of the depression and the growing, international economic crisis that accompanied the outbreak of general war in Europe.

There is not the slightest evidence that Franco ever proposed to implement the national syndicalist revolution of which radical Falangists talked."

"Nearly all confiscated or collectivized properties, urban and rural, were returned to previous owners or their heirs, "

"More serious than wartime destruction for the economy as a whole was the fact that Spain possessed little domestic capital that could be mobilized for reconstruction. The states gold reserves had been largely liqui- dated by the wartime Republican government,” it already held a considerable public debt, and the country lacked an efficient domestic capital market in which funds might be readily generated. A weak and inefficient fiscal system further limited public resources. Perhaps as much as 23 percent of Spanish industrial investment and bonds was held by foreigners. The major single source of imports was the United States, but Spain's largest export market was Britain, followed by France and Germany. Much of the pattern of international trade had been disrupted by the Civil War, and the subsequent European war made it unlikely that it could be easily restored. All this depressed opportunities to earn foreign exchange or negotiate foreign loans. Yet as matters stood, Spain would need foreign loans or credits in the short run to import vitally needed materials ranging from basic food supplies to cotton and other goods used in textile production, the largest domestic industry. The United States did grant credits for the importation of cotton, but Britain and France were willing to provide credit only on stringent terms, while Spains associates in Berlin and Rome had no extra capital to provide on any terms."

"Franco did have a reasonably consistent general orientation. He had grown up in the Regenerationist era of the early twentiethcentury and always believed that the government should itself provide a concerted approach to economics. More recently, he had been impressed by the achievements of Hjalmar Schacht's policies in Germany and was convinced that orthodox liberal theories had become passé. Franco preferred a policy of nationalism and voluntarism that subordinated eco- nomic affairs to state policy in all those areas which the state might deem important. Its goal would be achieving national development and as high a degree of self-sufficiency as might be feasible. In this regard he assigned a high value to raw materials, with which he was convinced Spain was abundantly supplied, while downplaying the significance of capital and technology. In August 1938 he had gone so far as to declare to a French journalist, “Spain is a privileged country that can be self-sufficient. . . . We have no need to import anything. * Later, in December 1939, he spoke of Spain’ opportunity to exploit untapped gold deposits, which he apparently was convinced existed."

"His basic ideas were outlined in an extensive document that he signed on October 8 entitled “Guidelines for a Plan of Reform for our Economy.” This laid out a vague ten-year plan to achieve economic modernization and self-sufficiency, proposing to simultaneously increase exports and re- duce imports without relying on foreign investment. It revealed great faith in the economic potential of Spanish society and the adequacy of do- mestic raw materials. The effectiveness of statist direction and control was simply assumed. The goal was to meet the country’s basic economic and defense needs primarily from domestic resources within only four years, another six being proposed as necessary to achieve full reconstruction and development."

"It proposed to eliminate the deficit in the external balance of payments within a decade, largely through a massive program of dam construction to boost electrical output and provide water for irrigation. The varied approaches to economics of the ideological “families” of the regime were as diverse and eclectic as the politics of the Nationalist elite in general. Falangists could present no clear, detailed program, nor did Franco wish to give any individual or group the power to develop or implement overarching policy. * It suited him to approach economic policy on an ad hoc basis, adding or dropping features or particular policies as circumstances warranted."

"Given the severe shortages afflicting the country, sig- nificant imports of food, petroleum, and raw materials were an absolute necessity. Autarchy therefore was directed toward improving the terms of foreign commerce and expanding domestic industry, where new projects were calculated above all in terms of foreign exchange costs. The autarchist industrialization drive was initiated by a decree of Oc- tober, 1939, creating the Law for the Protection and Development (Fo- mento) of National Industry, which provided a wide variety of incentives, tax benefits, and special licensing arrangements for creation of new facto- ries. A subsequent Law for the Regulation (Ordenación) and Defense of National Industry of November 24 declared certain industries worthy of particular assistance, and remained in effect for twenty years. It also stipulated that every firm receiving any form of state financial or economic assistance must give preference to domestic products and services."

"Autarchist policy was full of inconsistencies and loopholes from the start and soon resulted in grave distortions. In addition to the emphases of the INI, it stressed war industries, railroad construction and repair, ship- building, roads, machine-tool production, domestic hydrocarbons, nitrogen, and cotton.* While rigid controls were set up for foreign exchange, imports, and certain domestic products, these barriers meant that rather artificial terms of cost allocation had to be projected for industrial development, based at first on the levels of 1935. Lack of market or other adjustments resulted in costs and prices that were set in an increasingly arbitrary and unrealistic manner, fueling inflation and impeding growth. As shortages arising from World War II intensified, this would also lead to costly and fruitless efforts to find replacements for imported petroleum by extracting oil from shale and bituminous coal (the chief fossil fuel deposits in the peninsula) and in official support for a dubious Austrian inventor who proposed development of an absolutely artificial form of synthetic gasoline.

Equally important, it discouraged the government from seeking a maximum of loans, credit, and investment from abroad because of regulations against foreign capital participation and the general disposition of state policy. Even in the straitened circumstances of 1939-40 it would have been possible to generate more foreign credits and capital investment, but the regime’s approach was to beware of such opportunities and accept them only on the most favorable terms, depriving a struggling economy of the necessary support for expansion and new employment.”"

"agriculture, the basis of the economy, was severely neglected. The main instrument of agrarian policy during the war had been the Servicio Nacional de Trigo (National Wheat Service) designed to channel marketing and stabilize prices. This was maintained in the postwar period at the cost of state subsidies, but investment stagnated. Spanish agriculture failed to recover its pre-1936 production at any point during the years of World War II, due to the effects of the Civil War, bad weather, and restrictive state regulations,” remaining in general terms nearly 25 percent below the admittedly unusually high levels of 1934-35.

Almost as soon as the agrarian former Nationalist zone and the more urban former Republican zone were integrated in the spring of 1939, massive food shortages began to develop in the country as a whole. On May 14, 1939, general rationing of certain staples was imposed and maintained at varying rates for more than a decade. Food supplies were allocated through the new General Commissary of Supplies (Abastecimientos) and Transports (CAT), which put into operation an increasingly complex and arbitrarily bureaucratic labyrinth of controls and procedures.

Austerity and self-sacrifice were announced as keynotes of the new economic policy. Raw materials were similarly rationed or allocated for industry, and government controls soon produced a widespread straperlo (the word came from a government financial scandal in 1935) or black market, which operated on nearly all levels of the economy, from simple consumer goods to major industrial supplies. State allocation became subject to extensive manipulation and bribery. Arrests and even a few executions were later carried out, but corruption developed into a system of its own. What the tensions and ideals of wartime had largely avoided were produced on a massive scale in peacetime as a result of the acute shortages and state controls.” For ordinary people in the former Nationalist zone, at least, the immediate postwar years were in some respects worse than the war itself.

During the five years that followed the Civil War there were at least 200,000 deaths from malnutrition and disease over and above the prewar death rate. Pulmonary tuberculosis carried off at least 25,000 a year, while in 1941 there were 53,307 registered deaths from diarrhea and enteritis, 4,168 from typhoid fever, and 1,644 from typhus.*"

"The very conservative fiscal policies of the new regime reduced the percentage of national in come collected in taxes from 17.83 under the Republic to 15.07 during the first five years after the Civil War. Increased military expenses and war- time shortages left little for new public works, for example, that might have palliated unemployment. The percentage of the national budget devoted to public works declined from 14.04 under the Republic to 7.74 during the first postwar years. Official unemployment did descend from approximately 750,000 before the Civil War to 500,000 by the close of 1940 and eventually to 153,122 by the end of 1944, but such statistics hid the usual massive rural underemployment in parts of the country. In addition, wages remained extremely low and in real terms at first declined, as did the total labor force during the immediate postwar years (because of wartime losses, emigration, and a high rate of incarceration)."

Foreign Policy: The Neutral Phase, 1939-1940

"At the close of March 1939 Franco signed a treaty of friendship with Germany requiring mutual consultation in the event of an attack on either, and also joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, though the latter was a gesture without very concrete obligations. On May 8, the Spanish government officially withdrew from the League of Nations.

This did not mean that the Spanish regime was a satellite of either Axis power, for Francos policy from beginning to end was based on pragmatism and his judgment of Spain's best interests."

"War debts to Italy and Germany were a heavy obligation. Italy was owed more than 7 billion lire, but the amount was generously reduced by Mussolini to only 5 billion (around $250 million), partly with the aim of facilitating Italian economic penetration of Spain. After long and hard bar- gaining, the twenty-five-year table of payments was established to begin in mid-1942. Payment was eventually completed exactly on schedule on June 30, 1967."

"One government report prepared for Franco complained that “the Germans consider Spain a colony of theirs.” The Spanish regime for the most part avoided any further commitments and blocked greater economic penetration. Debt negotiations were strung out for the duration of World War II, and only very limited payments were made before the obligation was unilaterally canceled by Spain in 1945.

As tensions heightened during the summer of 1939, Franco used the phrase hábil prudencia (adroit prudence) to describe Spain’s foreign policy at a July meeting of the FET's National Council. The regime was trying to build closer relations with Spanish American states, the Philippines, and even the Arab world in an effort to reestablish the historic dimensions of Spanish diplomacy and circumvent its restriction to a weak and passive role in Europe."

"Hitler's signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact only two weeks after the formation of the new Spanish government was a shock to Madrid, contradicting the basic orientation of Francos policy. The Falangist organ Arriba could only headline it as a “Surprise, A Tremendous Surprise,” but at first was at a loss to justify it. The imminent outbreak of war was received with dis- may, for the Polish government was a Catholic national-authoritarian state that had much in common with Francos, and the Generalissimo and other Spanish leaders feared another civil war throughout Europe that would open the door to the Soviet Union, whose foothold in the Peninsula had been eliminated only six months earlier. Nonetheless, Franco apparently considered Poland at least partly responsible for the impasse with Ger- many, because it had refused any compromise over the Polish Corridor,"

"On September 3, when Britain and France declared war on Germany, Franco publicly called on all parties to reconsider their decisions and return to negotiation. His appeal for “voluntary limitation” of use Of means of destruction was not categorically pro-Polish, however, even though Beigbeder informed Berlin that renewed negotiations for a Spanish-German cultural agreement could not take place. Spains neutrality was announced the following day, and Franco followed this up by quietly denying opportunity for Germany to supply its submarines in Spanish ports."

"Strong sympathy was expressed for Finland when it was attacked by the Soviet Union in December. The Soviet attack had the effect of diminishing Germanys prestige in Spain, for Hitler was generally viewed as responsible for bringing the Soviet Union into eastern Europe, and a small amount of Spanish arms were subsequently made available to the Finns.

The new Spanish regime looked much more to Rome than to Berlin, seeing in Fascist Italy the nearest thing to a model. "

"In March 1940 the senior generals who made up the Consejo Superior del Ejército (Senior Army Council) approved a statement prepared by General Kindelan declaring it impossible for Spain to enter the conflict because it lacked economic support and materiel. They also complained of the extreme internal division within the FET and questioned its role as partido único, declaring that the Army was ‘the only available instrument for orienting Spanish politics.”

A new trade agreement was signed with Britain that month, granting the hard-pressed Spanish economy modest credits,* and on April 26 Beigbeder asked for British and French recognition of the territorial integrity of a neutral Spain and its possessions in the event that war spread, a recognition that was duly granted. Spain also signed commercial agreements with France and Portugal, and during 1940 had a greater volume of trade with the Allies than with the Axis, managing to pay off a portion of its wartime debt to Britain in pounds. However, Franco rejected the possibility of a 200-million-dollar loan from the United States for badly needed railway equipment, fearing it would compromise Spains freedom of action, and also spurned a French request in April 1940 for a pledge of continued Spanish neutrality in the event of Italy's entry into the war."

Tensions Within the FET and Syndical Organization

"Though most Army officers at least to some extent shared the Germanophile attitudes of Falangists vis- á-vis the European war, nearly all resented the bureaucratic monopoly of the FET, its ideological radicalism, and the elitist presumption of Falangist militants. Few officers took their membership in the FET very seriously, and almost all were gratified by the military decree of July 2, 1940, that reconstituted the Falangist militia strictly under military command.

Thoughout the World War II period, the most politically active figure in the military hierarchy was Aranda, who was overtly anti-Falangist. He had intervened several times as captain-general of Valencia during 1939 to moderate the repression after the city was occupied, and is even alleged to have executed several Falangists caught trying to drag Republican prisoners from military jails for summary execution.” Despite the Axis sympathies of most of the generals, during the months of “phony war” in 1939-40 they feared involvement in dangerous adventures, and Aranda's prestige increased. "

"Twenty of the draft's thirty-seven articles were devoted to defining the scope and structure of the proposed new corporative parliament, which was to be rather like that of Fascist Italy. The most controversial aspect was article 28, which declared, “The Junta Política is the supreme political council of the regime and the collegial organ of coordination between the state and the Movement.” Article 31 went on to stipulate, “The Junta Política must be heard in full session on matters that affect the constitutive power and the Fundamental Laws of the State, on international political treaties and concordats, on the declaration of war and the conclusion of peace. The competence of the Junta Política in those matters defined by the Statutes of the Movement remains unaltered.””:

This alarmed non- and anti-Falangists because it threatened to give the upper echelon of the Movement a constitutive place within the structure of state power, and it elicited a formal letter of protest from Esteban Bilbao, one of the most influential representatives of Carlism within the regime, against the “systematic interjection of the Party” in the organs of the state.”? Franco evidently agreed and ordered the project shelved.

Less easily short-circuited was the plot against Franco that had begun to gestate among a small core of camisas viejas. It has been estimated that as much as 60 percent of the original membership of the party had been killed during the war, but the vast majority of the surviving Falangists had remained in the FET, some in hope of being able to dominate the new structure and implement the original Falangist program. In the aftermath of the Civil War it had become clear that the new regime was essentially a rightist authoritarian system flavored with fascist rhetoric but little more, and a few decided to try to take action. Their attitude reflected that of a German diplomat who replied to the question “How do you find the new Spain?” by saying, “When I find it, I shall tell you.””"

"At the close of 1939 a small group met at the home of Col. Emilio Rodriguez Tarduchy, a veteran of Primo de Rivera’s UP, the UME of 1933, and the original Falange. A clandestine junta politica was formed, with Tarduchy as president and Patricio González de Canales, a militant young camisa vieja from Seville (who held posts in Falangist publications and state commercial administration) as secretary. Seven or eight other veterans, representing various small sectors of the Falange in diverse parts of the country, formed the rest of the junta's fluctuating membership.” Their most coveted ally would have been General Juan Yagiie, who was close to José Antonio de Girón and other key elements of the Falangist ex-combatientes but refused to move directly against Franco, insisting that the Falange must change the regime from within. Though the conspirators later claimed to have gained the support of several thousand Falangists in various parts of Spain, most of this was doubtless quite tenuous, and they completely lacked influence among key power holders.”

The clandestine junta then turned to outside support and especially to Hans Thomsen, Nazi Landesgruppenleiter for the NSDAP organization among German residents in Madrid. Thomsen, however, would or could offer German support only on terms that would have reduced Spain to the status of a satellite, while the conspirators were further discouraged by rumors that an opportunistic clique of rightist dissidents was also intriguing for German assistance. The German government is said to have refused its aid unless the Falangists would agree to place themselves under the direct orders of the Fuehrer.”"

"The Falangist plotters nonetheless continued their meandering course. After toying with and rejecting the notion of assassinating Serrano Súñer, they finally decided to face up to their only direct alternative—the assassination of Franco himself—at a final meeting in Madrid near the end of March 1941. They concluded that there was no one with whom to re- place him and that Falangism lacked the support to do without him. In a meeting attended by five conspirators, the vote was four to nothing, with one abstention, against attempting assassination.” The conspirators attributed their failure to gain more support to the success of Gamero del Castillo in attracting Falangist veterans to positions in the bureaucratic structure of the regime."

"Salvador Merino was a rather cold, highly ambitious Falangist—and apparently an ardent Naziphile—who conceived the ambition of building a powerful and relatively autonomous syndical system as the decisive element in the new regime...On Victory Day, March 31, 1940, the first anniversary of the end of the Civil War, Salvador Merino arranged for several hundred thousand workers to march in a gigantic Madrid parade,* drawing the ire of Army right-wingers. "

"Full national syndicates were declared to have been organized in ten sectors of the economy—the most important being textiles and metallurgy—by the close of 1940, yet the number of workers organized totaled only about 110,000 in Madrid, possibly 300,000 in Barcelona, and approximately 107,000 in the mining and industrial province of Asturias.*"

"Merinos principal inspiration seems to have been Nazism, and he evidently aspired to a leading role in the radical transformation of Spain...In July 1941 Salvador Merino was relieved of his post and sent into internal exile in the Balearics, and thus the most ardent pro-Nazi in Spanish government vanished from public life."